On this special day, we interviewed the early career scientist Dr. Grace Androga , from Malawi, who told us her story on the fight against antimicrobial resistance in the first person.

Dr. Cláudia Vilhena, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen Nürnberg, Bacterial Interface Dynamics lab

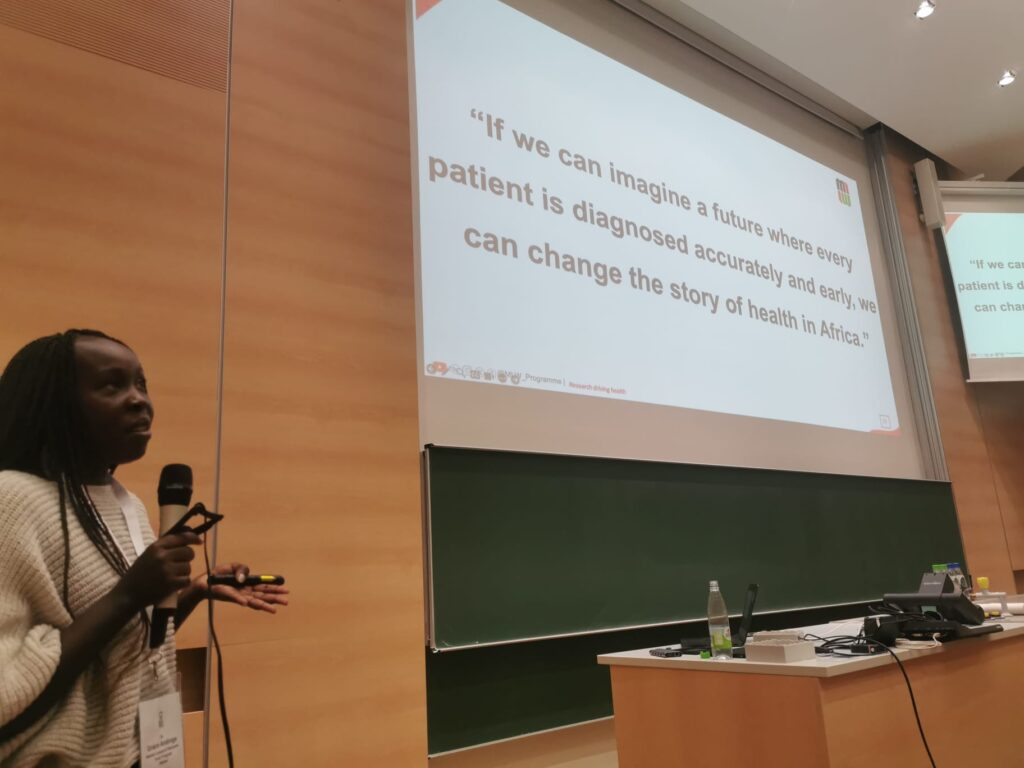

I had the pleasure of meeting Dr. Grace Androga in person at the 4th Women in Science Symposium in Erlangen in Erlangen in the fall of 2025. Her work on antibiotic resistance immediately stood out, not only because of its scientific depth, but also because of the clarity of its purpose. Grace's path to science began far away from the institutions where global research agendas are often shaped. Growing up as a South Sudanese refugee, she experienced firsthand how fragile access to healthcare and diagnostics can be. Today, she works at the intersection of diagnostics, genomics, and AMR in African health systems, embodying a form of scientific leadership that is both rigorous and deeply rooted in lived reality. I invited her to this special interview on the occasion of the International Day of Women and Girls in Science to share a much-needed perspective on AMR.

Cláudia Vilhena

Bio

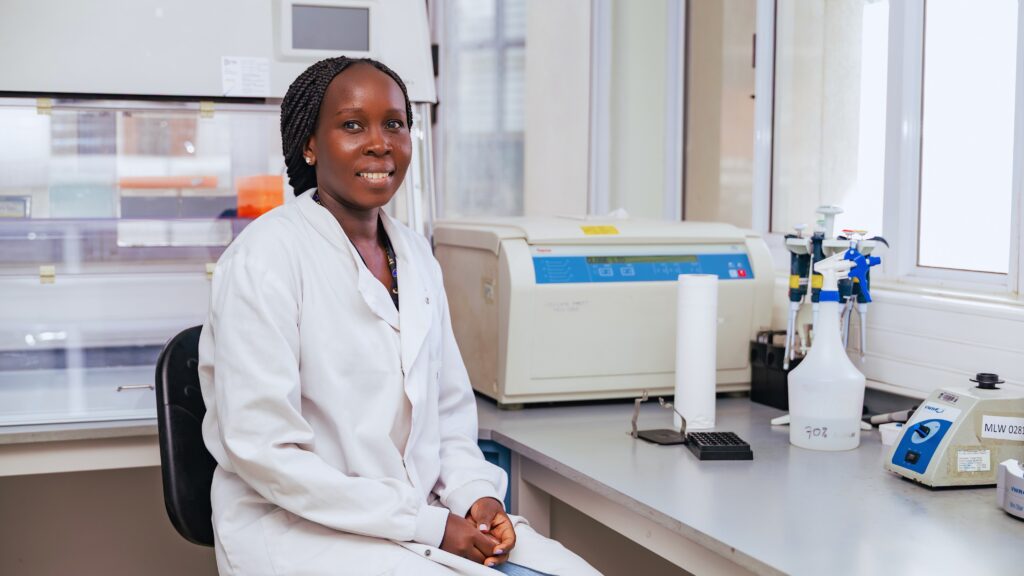

Dr. Grace Androga is a Wellcome Early Career Fellow at the Malawi Liverpool Wellcome Programme, where she works on anaerobic pathogens, molecular diagnostics, and genomics. From her early days as a medical scientist, she was drawn to the transformative power of accurate diagnostics, tools that can change patient outcomes and save lives.

Her doctoral research on Clostridioides difficile laid the foundation for a career focused on translating lab discoveries into real-world impact. Clostridioides difficile laid the foundation for a career focused on translating laboratory results into practice. Since then, she has used her expertise to understand infections of the central nervous system and bloodstream, often working in African healthcare systems where access to diagnostics can mean the difference between life and death.

Since then, she has applied her expertise to understanding central nervous system and bloodstream infections, often working in African health systems where access to diagnostics can make the difference between life and death.

As an African Early Career Researcher returnee, Dr. Androga is passionate about developing practical diagnostics for low-resource settings, strengthening local research capacity, and championing women’s leadership in science. For her, science is not just about discoveries, it’s about making those discoveries matter where they are needed most.

For her, science is not just about discoveries, it’s about making those discoveries matter where they are needed most.

CV- You work in AMR. Could you tell us a little about what AMR is, what your work/project consists of and your journey into AMR?

GA- Antimicrobial resistance, or AMR, is essentially the ability of microbes to survive the drugs we use to treat them. It’s a natural phenomenon, but human practices such as the overuse of antibiotics, gaps in infection control, and uneven access to diagnostics, accelerate the problem. My work sits at the intersection of understanding how resistance emerges, how it spreads, and how health systems can respond effectively.

My journey into AMR wasn’t planned from the start. Early in my career, I was drawn to infection biology more broadly, fascinated by how pathogens interact with the human body and with each other. Over time, I became increasingly aware of the scale and urgency of AMR, particularly in African settings where the burden is high, but data and resources are limited. That gap between scientific knowledge and practical, locally relevant solutions became the focus of my work.

From there, my career evolved naturally combining laboratory research, field studies, and collaborations with clinicians, policymakers, and fellow scientists.

„"It’s a path that constantly reminds me that AMR is not just a scientific challenge, but a societal one, and addressing it requires both rigorous research and the kind of local leadership that ensures solutions are sustainable and meaningful."„

CV- How did your background and early life experiences influence the scientist, and the person, you became?

GA- Growing up as a South Sudanese refugee had a profound impact on both who I am and how I approach science. Life was unpredictable, resources were scarce, and opportunities were never guaranteed. Those experiences taught me to be resourceful, to question assumptions, and to pay attention to the realities that many scientific studies omit. I learned early on that knowledge is most valuable when it can make a real difference in people’s lives. At the same time, that background shaped me personally. It instilled resilience, curiosity, and a quiet insistence that challenges are often structural rather than personal. It made me conscious of the gaps between talent and opportunity, and motivated me to try, in my own way, to create spaces where others can thrive. Those lessons continue to guide how I mentor, how I collaborate, and how I think about leadership.

„Science, for me, is never just about data or experiments; it’s about people, communities, and the broader systems we are trying to improve.„

CV- As a woman in science, particularly in infectious biology, what were the biggest obstacles you faced?

GA- I think many of the obstacles I’ve faced are not unique, but they are certainly amplified for African women in science. Early on, there were low expectations, sometimes explicit, more often implicit, about what I could lead, how ambitious my work could be, or how seriously my expertise would be taken. There is also the cumulative burden of being one of very few women, and often the only African woman, in certain rooms. I didn’t overcome these challenges by trying to be exceptional at everything, but by being very clear about the questions I cared about and by building work that was rigorous, relevant, and difficult to ignore.

I also learned early the importance of choosing collaborators and institutions that valued intellectual generosity and integrity. Finally, mentorship, both receiving it and later providing it, has been essential. Systems don’t change because individuals endure them quietly, they change because people make room for others as they move forward.

CV- Many young scientists, especially women from underrepresented backgrounds, struggle with confidence or belonging. What advice would you give them?

GA- Feeling uncertain or out of place is not a personal failing, it is often a rational response to systems that were not designed with you in mind. My advice is to separate confidence from competenceYou do not need to feel confident to do excellent science. Focus instead on developing clarity about your questions, your methods, and your values. At the same time, be intentional about community. Find people who take your work seriously and who are willing to be honest with you. And remember that belonging is not something you wait to be granted, it is something you build through contribution. Over time, the work speaks and it reshapes the space around you.

CV- How do you see the role of women in infection biology evolving in the next decade?

GA- I think the role of women in infection biology is expanding, but unevenly. We are seeing more women leading strong scientific programmes, shaping policy, and influencing how research questions are framed, and that matters. It changes not just who is visible, but what kinds of problems are considered important and how success is defined. That said, representation alone is not progress. Many of the underlying structures e.g. funding models, evaluation metrics, and leadership pathways, still reward uninterrupted, linear careers and undervalue collaborative and applied work. So, while we are moving in the right direction, major structural changes are still neededif we want participation to translate into power, sustainability, and impact. The next decade will be defined less by whether women are present, and more by whether the system is willing to change in response to that presence.

CV- If you could give one piece of advice to a young woman starting her scientific journey in 2026, what would it be and why?

GA- I would tell her to be intentional about the choices she makes early on, because those choices shape not just her career, but how she experiences science.Look for mentors who challenge you, environments that respect your curiosity, and projects that excite you, not just those that look impressive on paper. Don’t let anyone define what your journey should look like. At the same time, be patient, persistent and open to learn. Progress is rarely a straight line, and you will encounter moments where the system doesn’t seem to be on your side. Use those moments to learn, to strengthen your thinking, and to define what success means for you personally. Do work that is meaningful to you, because influence and opportunity follow purpose and excellence more reliably than they follow expectations imposed by others.

CV- Who is Grace Androga, outside the lab?

GA- Outside the lab, I look for balance in quiet, ordinary ways. I read novels, histories, stories that make me see the world differently, that make me pause and wonder. I walk sometimes, or just spend time outdoors, because it reminds me there is life beyond experiments and data. I love music and drawing, and I’ve recently started painting. In those quiet moments, ideas surface in ways they never do in the lab - slowly, unexpectedly, and with a kind of freedom that only comes outside of science

Gardening and cooking are other passions. There is something humble and profound about nurturing life, growing a plant, preparing a meal, and sharing it with friends and family. It reminds me, in the simplest way, of the communities that science exists to serve.

These practices do more than recharge me. They shape how I think, how I see the world, how I approach questions and collaboration. Curiosity, patience, and care are not just for life outside the lab, they carry into the lab, into research, into the work itself. They are the invisible threads that connect what I do to the people it touches.